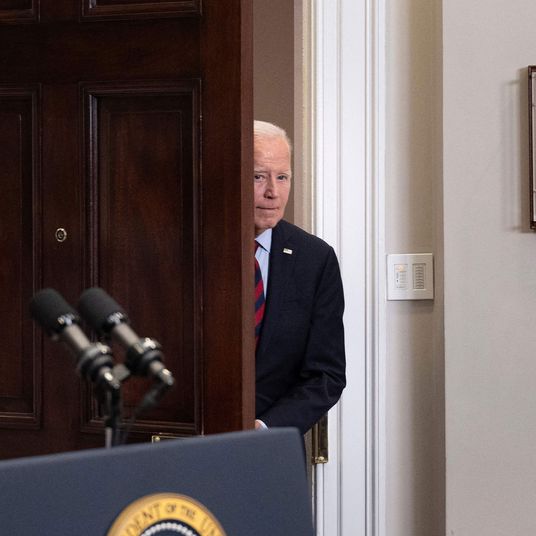

In theory, it should be enough that he is a certified loser. Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump once before, and it could happen again. In that election, Trump’s major liabilities were his mismanagement of the coronavirus pandemic and its related economic fallout. For this one, he is campaigning in between stops on a national tour of court appearances and arrest dates. The risk for the Republican Party is not just that history will repeat itself but that it will elaborate.

Yet with each successive indictment, Trump grows stronger. His support deepens. It has always been true that Trump’s fans see him as their id. Now, his legal troubles have had the effect of turning this very rich and powerful man into a proxy for anyone who feels like the victim of a conspiracy cooked up by the system. Outside the courthouses where he stands accused of fraud and election interference and mishandling of classified documents, among 91 felony counts in four criminal cases, they tell you this is all playing out exactly as they suspected, just as Trump said it would. The deep state had set him up, and now it would hold its trials. In the official Donald J. Trump campaign store, he sells the image of his persecution, his mug shot splashed on merchandise that says NEVER SURRENDER and NOT GUILTY.

The other candidates made decisions to run informed by political science and traditional experience. Trump would not enter the race, the thinking went, because his term in office had ended so poorly, and if on the off chance he did run, he would be rejected. Just as in 2016, these calculations did not appreciate that Trump is not a political phenomenon. He is better understood as a celestial event, like the appearance of a black hole. Everyone in his orbit is defined in relation to his gravitational pull.

Cover Story

The Trump campaign complains that the media is rooting against him, paying mind to candidates who have not performed well enough in polling or fundraising to demand serious coverage. The other candidates complain that the press is so convinced that Trump’s nomination is inevitable that it’s like there is no primary. And it does often feel that way.

Up close, then, the Republican contest is a strange sight. Over the past 13 weeks, I have visited the early-voting states to observe the candidates. They host few events, sparsely attended by the press and moderately attended, at best, by voters. There is no “campaign trail” in the traditional sense. There is instead activity scattered here and there, interspersed with long periods of stillness. Often, it does not feel like the candidates are really running. It feels like they are doing something else.

They tiptoe around the major issues, living in fear of the front-runner whom they have to kill off if they are to have any chance, waiting instead for him to die of natural causes. They attack Biden or Kamala Harris, or they attack one another, and when they do attack Trump, with rare exceptions, they seem to wince. At campaign events, most candidates do not mention him by name at all. They’re too scared. Too uncertain about their place in a conservative movement wholly captured by him. And even when they manage to draw a spotlight, getting booked on cable TV or for network sit-downs, they face the humiliating reality that they have been cast as supporting characters in The Trump Show. They are asked to comment on the latest developments in the star’s various dramas — appearances in which they help to defend him against what they call a politicization of the justice system.

Their essential function is to provide yet more content about the American political media’s favorite subject. Whether the candidates are pretending he doesn’t exist, or flattering him to pander to his fans, or calling him unfit to lead, all of their campaigns have one thing in common: They cannot escape Donald Trump.

Mike Pence in the FunZone

Sioux City, Iowa

Mike Pence swallowed hard. He straightened his posture and looped his thumbs around his belt and into the front of his khakis. His grip was firm, his knuckles white. He forced a calm expression across his face. He shifted his weight from foot to foot. Eyes locked on the voter, an older woman who first thanked him for his service to the country, he blinked slowly and nodded.

Thirty-five years since his first political campaign and still it appeared to require all of his strength, so help him God, to stand here in the Pizza Ranch FunZone Arcade in Sioux City, Iowa, where the first caucus will take place in January and perform an impression of a man who, through the noise of nearby gamers blowing each other’s brains out in Halo: Fireteam Raven, was listening thoughtfully and seriously. A man who was not at all annoyed by what he was hearing and not at all disappointed to see that so few people had shown up to meet him.

Then the inevitable began — the doom-loop questions about January 6. “You were commenting on the fact that all of these problems belong to Joe Biden, and they do,” the woman told him. “However, uhhm, if it wasn’t for your vote, we would not have Joe Biden in the White House.” Elsewhere in the room, a man called out. “Right!” he said. Pence angled his head to the right. If nothing else, he had practiced how to handle this exchange. He angled his head to the left. The woman continued: “Joe Biden shouldn’t be there, and all those wonderful things that you and Trump were doing together would be continuing and this country would be on the right path. Do you ever second-guess yourself?” She was speaking clearly and forcefully now, her finger pointed at her target. “That was a constitutional right that you had, to send those votes back to the states!”

Pence took a deep breath. “Well, let me speak to that issue — ” The woman talked over him. “You changed history for this country,” she said. “Yeah,” he said. “Let me speak to the issue, ’cause I think it’s an issue that continues to be misunderstood, but I know by God’s grace I did exactly what the Constitution of the United States required of me that day, and I kept my oath.”

At this, many of the people in the room applauded, and their approval seemed to soothe Pence. He went on: “But let me be very respectful of the question and tell you, look, states conduct our elections. You never want to let Washington, D.C., run elections. You certainly would never want one person in Washington, D.C., to decide who the president of the United States should be.” The woman cut in: “You wouldn’t decide. You were just sending it back to the states!”

Another deep breath. “Ma’am,” Pence said. “Here, let me explain it to you.” He went on to detail the process for conducting recounts and his perspective on the minor irregularities in the 2020 election and how results are certified. “Don’t take my word for it,” he concluded. “Go read the Constitution.”

Oh no. He had been doing so well, but as he lectured on the particulars of the process, he grew frustrated, and now he was at risk of sounding condescending by ordering a confused old woman to read the document to which she referred — an implication that she wasn’t very good at reading or that she had, in fact, never read it.

He caught himself. “Really,” he told her, “really, I say this with great affection and respect. The Constitution’s very clear. My job was to oversee a session of Congress where objections could be heard, and I made sure that objections would be recognized so we would hear whatever evidence or whatever debate there was. But the Constitution says you open and count the votes. No more, no less.” He continued in that vein. Then the necessary kicker, the requirement to say his old boss’s name, even though Pence tends to avoid doing so: “I said before, I said when I announced, President Trump was wrong about my authority that day, and he’s still wrong. I believe it with all my heart.”

In the two and a half years since a mob attacked the Capitol and threatened to assassinate Pence over his refusal to stop the certification of the election Trump lost, many Americans have grabbed scissors and markers and cans of spray paint and where there was once TRUMP/PENCE, there is now, often, only TRUMP. The name of the former vice-president torn off, crossed out, covered over, or otherwise defaced on campaign placards and bumper stickers and handmade murals in pure expressions of fury. (Karen Pence, as it happens, used her platform as Second Lady to promote art therapy.)

The Pence campaign is premised on the theory that not everyone feels this way. That a demographic of voters exists who want to reinstall the Trump administration but will not vote for Trump again. In this scenario, it is logical that Pence, who stood loyally by Trump’s side until January 6, would inherit their support. In a normal world, after all, a vice-president would be the natural heir of the political movement attached to the president he served. In a normal world, of course, the president in question would not have been indifferent-verging-on-sympathetic to the suggestion that his vice-president be hanged. “I’m not convinced that the people who rooted for and attacked the Capitol are representative of primary voters for Republicans,” Marc Short, a senior adviser to Pence, told me. “I don’t know if that percentage that, as you say, wanted to murder him are necessarily voters that he’s appealing to.”

Yet the polls do not suggest such voters exist en masse. A year ago, Pence hovered at third place in the high single digits nationally, but those numbers shrunk as the field expanded. He maintains only a marginal lead over Chris Christie, Tim Scott, Doug Burgum, and Asa Hutchinson. Short said the campaign is hopeful that 2024 will play out as previous cycles did, with Iowa breaking late for candidates who maintained underwhelming numbers for long stretches before Caucus Night. He named Rick Santorum and Mike Huckabee, two men who did not come close to getting elected president, as examples of this phenomenon. In Iowa, where Pence is not polling anywhere near as high as Santorum or Huckabee once did, and where he has spent time courting the Evangelical voters of the rural Northwest on a Roe v. Wade victory lap that Trump is sitting out, he has barely cracked 3 percent.

Pence likes to tell voters, “Different times call for different leadership.” In the FunZone, he added, “If we spend this election talking about the past, you’re gonna get four more years of Democrats in the White House.” A man looked on from under the brim of a white cowboy hat that read TRUMP 2024.

PENCE was nowhere in sight.

Ron DeSantis at an Old Textile Mill

Newport, New Hampshire

If nothing else, Ron DeSantis was definitely safe. At a town hall in a rehabilitated former mill near the Sugar River in western New Hampshire, the voter-to-security-guard ratio was about five to one.

The crowd was younger on average than, say, the typical audience at a MAGA rally — there were people in their 30s and 40s with families — but it was also a fraction of the size. Youngish voter, youngish voter, baby, another baby, youngish voter, security guard. Middle-aged voter, youngish voter, older voter, baby, middle-aged voter, security guard. Older voter, baby, another baby, middle-aged voter, toddler, older voter, security guard. And so on. The guards — bearded, buff, and tattooed, like UFC fighters — stood with menacing glares and folded arms, infecting the room with the same tense energy that animated the candidate.

It was late August, and with his numbers in New Hampshire in free fall, DeSantis was devoting the weekend to opening an emergency parachute. Talking to the local press, he did his best to sound humble. His PAC could and probably would pay a zillion campaign workers to knock on another hundred-something-thousand doors, but the path forward, he said, would be through his own small and meaningful contact with voters. On the final stop of a two-day bus tour, he arrived at a tiny stage inside a historic Newport mill to try to make a second first impression.

Up close, the operation mostly looked, well, expensive. His enormous security presence was matched in numbers by aides with clipboards and staff on hand to traffic-cop the parking lot. But a Bugatti will get you where you’re going only if you know how to drive it. Earlier in the summer, DeSantis had burned through his cash reserves with excesses that included $279,000 dropped at the Miami Four Seasons. To offset the spending and cover unpaid bills, DeSantis fired dozens of employees in what was described as a reset. He had been a declared candidate for all of nine weeks.

“One of the things you can know about me is I don’t go out and just flail around and say things that I know will never come to fruition. If I tell you I’m gonna do something, it means I’ve thought about it, and it means I will follow through with it,” he said. “You go down in Florida, even people that have been in the political opposition will acknowledge, if the governor says he’s gonna do something, he’s gonna do it. So buckle up.”

Nobody clapped. His speech was quick, his intonations stiff and unnatural, like those of an office manager giving a PowerPoint presentation. He moved right along. “I can tell you this: that, as president, on day one, we are going to stop the madness at our southern border once and for all,” he said. “We are gonna solve the problem.” Now people cheered. He stopped to take it in. “Day one, we’ll declare the border to be a national emergency,” he said.

He was only just winding up. Like so many Republican politicians, DeSantis was a student of Reagan, but unlike many of his rival candidates, to their great detriment, he was also a student of Trump. And among the lessons of Trump’s political rise was to take seriously the power of fear and the promise of catharsis.

“When we’re in charge, we’re gonna treat the drug cartels like the foreign terrorist organizations that they are,” he said. “We’re gonna authorize the use of deadly force. If they’re bringing fentanyl into our country … They try that when I’m president? We’re gonna shoot ’em stone-cold dead.”

This was supposed to be working. DeSantis was supposed to be the leader of his party. Fox News, once an extension of the Trump communications apparatus, had defected to DeSantis. With its help, his crusades against “wokeness” and COVID lockdowns had defined pandemic-era conservative politics, and as the pandemic era met the end of the Trump era, it seemed obvious that DeSantis would also define what came next.

To his credit, Trump called it. In May, on the green at the Trump National Golf Club in Sterling, Virginia, the former president was asked to comment on DeSantis’s campaign announcement. “I don’t care,” Trump said. “I think he’s very disloyal, but he’s got no personality. If you don’t have personality, politics is a very hard business.”

As a matter of reflex or of strategy, Trump has continued to laugh DeSantis off. “The problem for Ron DeSanctimonious is that, other than being a tribute-band or discount-rack version of President Trump, there’s no reason for him to run,” Trump senior adviser Jason Miller told me. In the spoken and written word, the campaign refers to DeSantis exclusively by Trump’s preferred derisive nicknames, often multiple times within the span of a single thought or sentence. Miller added, “Other than DeSanctimonious’s hopes and prayers that a political meteor would hit the Earth and somehow wipe out President Trump’s chances of winning, there has never been a plausible pathway to victory for Ron DeSanctimonious.”

The Trumpiness of it all is hard to ignore. DeSantis — looking with his boxy frame, deep-bronze tan, and red tie as if Scorsese had reverse-aged Trump the way he did De Niro in The Irishman — promises to lead what he calls “Our Great American Comeback.”

His ideas hardly deviate from the Trump Doctrine, and when they do, it doesn’t seem to help. Earlier this summer, the campaign was forced to delete a weird video that compared Trump’s statements on LGBT issues to the anti-LGBT policies enacted by DeSantis, who was depicted with lasers pointing from his eyes, which even some conservatives denounced as homophobic.

It was the kind of thing — a campy, extremely online, offensive self-generated meme — that Trump could post and get away with easily. The difference is that DeSantis is running a campaign and Trump is performing a magic act, and when DeSantis endeavors to cast the same spell, he bungles the delivery. It is as if he has only read about Trump but never seen or heard him, missing entirely the avant-garde quality that makes the whole thing click.

Trump has always claimed to hate the press, but DeSantis went further. He acted like it. In the early part of the campaign, he kept himself closed off to everyone outside the sympathetic conservative media. Interview requests were not just denied but sometimes met privately with insults. Amid his reset, he changed course, but it was too late to set the terms of the coverage himself.

His coming out as a candidate on CNN, a big interview with Jake Tapper, was overshadowed by Trump’s announcement that he was a target of special counsel Jack Smith’s January 6 investigation. DeSantis spent the first part of the interview defending Trump against political persecution. On The CBS Evening News, Norah O’Donnell began with this: “Governor, thank you so much for doing this interview. I want to talk about the state of your campaign. You have spent about $50 million so far, and you’re about 50 points behind Donald Trump. Are you running out of time?” Even on Fox, he can’t catch a break. Neil Cavuto: “Many people have given up on you, and I’m wondering if you’re concerned about that.” DeSantis: “That’s not true!” When DeSantis appeared on Real Time at the end of September, Bill Maher cracked, “Let’s face it, Ron. If the campaign was going well, you wouldn’t be on this show.”

Like Pence, the DeSantis campaign is hoping things will start to get better in Iowa. According to the New York Times, he plans to move a third of his staff there from Tallahassee to prepare for the caucuses. “It will all start to be viewed through the lens of Iowa,” Kristin Davison, COO of Never Back Down, DeSantis’s super-PAC, told me. “Trump is almost antagonistic to the voters in the state, hitting the popular governor, demeaning the pro-life voters in the state, and it’s really, really starting to hurt him. Conversely, the state is perfect for a candidate like DeSantis.”

Also like Pence, DeSantis is clearly hoping that abortion will save him here. Although Trump’s appointments to the Supreme Court led to the fall of Roe v. Wade, he has expressed dismay at the consequences of his own actions. During an appearance on Meet the Press last month, he called the six-week abortion ban DeSantis signed into law a “terrible thing.” Kim Reynolds, the governor of Iowa, took offense. Over the summer, she had signed a similar so-called heartbeat bill into law. “It’s never a ‘terrible thing’ to protect innocent life,” she said.

DeSantis was gleeful. Reynolds is popular in her state. When she declined to make an endorsement earlier this summer, Trump responded in anger, kicking off a feud that has dragged on for months. DeSantis, meanwhile, has been shrewd and patient, appearing with her at events and telling the press he would consider her for VP. “I applaud Governor @KimReynoldsIA and the Iowa legislature for promoting a culture of life,” he wrote on X. “Donald Trump is wrong to attack the heartbeat bill as ‘terrible.’ Standing for life is a noble cause.”

The following day, at a rally in eastern Iowa, Trump, who was publicly pro-choice until his first campaign for the Republican nomination, compared his current views on abortion to those of Ronald Reagan, a Christ-like figure in popular conservative mythology. Like Reagan, he said, he is pro-life with exceptions for rape, incest, and when the life of the mother is at risk. The crowd in Dubuque, a progressive city on the Illinois border, cheered. Trump left the rally and made his way to a pub where he handed out pizza and posed with fans. A blonde woman in a white tank top leaned over the bar for an autograph. He grabbed a marker and scribbled his signature across her chest.

Vivek Ramaswamy at a Pizza Ranch

Orange City, Iowa

Another day, another Pizza Ranch. It was a Friday afternoon in early September, and the parking lot at the chain restaurant was so full that cars piled up on the grass. Inside, several hundred people crowded into the booths and stood shoulder to shoulder at the salad bar, craning their necks to get a better look at Vivek Ramaswamy.

A 38-year-old biotech entrepreneur turned anti-woke activist, Ramaswamy had trolled his way to media stardom at the first primary debate through hyperactive Trumpian tactics that deeply annoyed many of his rival candidates, who huffed that this mirror-world image of Pete Buttigieg was a rookie who reminded them of an AI or Barack Obama.

A political outsider rich enough to claim independence from the influence of the donor class, Ramaswamy accused the other candidates of corruption. Christie was just angling for a new TV gig, he said. He wished Haley luck in her future endeavors working for defense contractors. Without Trump onstage, Ramaswamy became his surrogate. He even wore a shiny red tie.

For his efforts, Ramaswamy earned precious attention, generating over 1 million Google searches for his name in the 24 hours after the event. Two weeks later, the hype was still palpable in Orange City, Iowa, as he pitched voters on his plan to abolish federal agencies, including the FBI, and to “drill, frack, and burn coal” and never “apologize for capitalism.”

The campaign strategy is in part about volume. He says “yes” to every interview and maintains the busiest schedule. This is thanks in no small part to the fact that he owns a plane. He departs Ohio, where he lives with his small family, and pops over to Iowa, then on to New Hampshire. Though he does also have a bus, and it’s wrapped in a beige decal meant to look like the Constitution. On its side, it says TRUTH.

But mostly the strategy is about Trump. Ramaswamy is perhaps the most clear-eyed of all the candidates. “Whoever wins this race is going to require a meaningful portion of the MAGA, America First base to come with them. That’s just a fact,” he told me. “There’s no other version of winning,” he said, besides a campaign that “includes and respects that voter base.” He would know, he added, because “I’m part of that voter base.”

When he goes on about what “an excellent president” Trump was and how unfair the charges against him are, the question arises: If he’s so great, then why are you running? Ramaswamy is the first to admit that it’s Trump’s party. Why pretend otherwise? “And right now, he is by far in the lead,” he said.

While others whine about how it’s always “Trump this” and “Trump that” and “Trump, Trump, Trump” all the time, Ramaswamy shrugs with a certain finance-bro realism. Of course the narrative is focused on Trump: “Until the polling gap is closed, or at least partially closed, I think that’s just how it’s going to be.” In all likelihood, Trump will win the nomination. But if he doesn’t …

Outwardly, Ramaswamy theorizes there is a nonzero chance that voters will decide to carry out their own succession plan for the MAGA movement. They will determine, he hopes, that he is next in line. “Other than Donald Trump, I am the only candidate who unapologetically embraces true America First principles. Now, between Donald Trump and myself, I have something that he doesn’t: I’m young. I have fresh legs,” he said. “My path would have to run through persuasion of the base that I am better suited than Trump to carry that agenda forward.”

What Ramaswamy can’t say aloud is that there is a timeline on which his fate is determined by something other than the agency of those voters. If Trump is taken out by any of the million threats to his ability to run and hold executive office, those voters will not just seek an alternative, as the other candidates hope. They will seek Trump’s best proxy.

Before he saw the light on the futility of criticizing the former president or contradicting reality as he defines it, Ramaswamy did both. In his first book, Woke, Inc., Ramaswamy described the “angry mob of rioters” who “stormed the U.S. Capitol” on January 6 as “a disgrace” and “a stain on our history.” He rejected, he wrote in his second book, “the victimhood narrative of a stolen election.” Confronted on the debate stage by Christie, who accused him of having “said very different things” about Trump in his books, Ramaswamy said, “That is not true!”

Ramaswamy is too careful not to offend Trump’s supporters to ever claim he’s a better Trump than Trump. What he says instead panders rather artfully. “The America First movement started with George Washington,” he told me. (And actually, Trump would love that.) “America First does not belong to any of us. It belongs to the people of this country. It’s bigger than Trump. It’s bigger than me.”

Chris Christie in Scott Brown’s

Rye, New Hampshire

Chris Christie walked through the barn in Rye, New Hampshire, his iPhone sticking out of his dress shirt’s monogrammed breast pocket. He made his way to the back of the room and stood before a banner that advertised SCOTT BROWN NO BS BACKYARD BARBECUE. It was raining, so in addition to no bullshit, the event was not in the backyard.

It was September 11, and as he introduced his guest to the crowd, Brown, the former Massachusetts senator and, under Trump, the U.S. ambassador to New Zealand and Samoa, mentioned the relevant biographical detail that Christie had experience in law enforcement, though Brown did not remember exactly what kind of experience it was: “Obviously, his time as a — uhh — you know, working in the — uhh — in the law-enforcement field.” He paused. “At the senior level. He’ll talk to you about that. He obviously knows a lot about crime, criminals — uhh — the justice system itself. Uh, y-y-you were, you are, uhhh — ” Brown said. “Was it just for New Jersey?” Christie looked disappointed. He nodded. “The whole state,” he confirmed. “The whole state,” Brown said. “Yeah. Obviously did a great job there.”

Christie used the moment to his advantage. “We have great criminals there,” he remarked, deadpan. The crowd laughed.

Christie is running a single-issue campaign on the idea that Trump is unfit to hold office. In the barn, he said, “I’m not somebody who was a Never Trumper. I wasn’t. But you have to meet a certain standard in your personal conduct and your political conduct, and if you don’t meet that standard — put aside the criminal charges. You can agree with them or disagree with them, and there’s some I agree with and some I disagree with. But the conduct is unacceptable.”

And he’s running a single state operation, ignoring Iowa as he did in 2016 (where he placed tenth) to bet it all on New Hampshire (where he placed sixth). Earlier in his political career, before the notion of bipartisanship became toxic on the right and before he embraced Trump for the duration of his presidency until January 6, Christie had proved adept at playing nice with Democrats. He is hopeful he can appeal to them now and persuade the wide range of voters eligible to participate in New Hampshire’s open primary that he is the best chance they have of blocking Trump’s path.

“Christie got into the race polling at a certain level back in June — which was pretty low, zero to one percent,” said an adviser to Christie. “He has been steady and consistent over a period of time.” Despite his efforts, he has yet to crack double digits. Stuck in fourth place in New Hampshire just behind DeSantis, whose numbers have been on a downward spiral since April, and Haley, who has surged by ten points in the past few weeks, and Trump, of course, who is comfortably in the stratosphere, 30 points ahead and rising.

“No one knows if this will work because it’s never been done before,” the Christie adviser said, “but in our estimation, it’s the only way, potentially, to actually do it.” The strategy, the adviser admitted, depends on an outcome in which a majority of voters end up being “people who don’t show up in polling.” It’s crucial to Christie’s strategy to lower expectations and sow doubt about the polls. “Here’s what I promise you,” he told the crowd. “I will not lead in New Hampshire in one poll — not one — until Election Night.”

Christie has spent much of the past several years as a political pundit under contract with ABC, and he is good at it. Here, he offered a rapid-fire assessment of the dynamics between the candidates and the front-runner: “He has lots of awful, horrible things to say about me. Seems like the only two people he says anything bad about are me and Ron DeSantis. Why? Because he thinks we’re the only two who could possibly beat him. You won’t hear him say it, though. Vivek is practically his running mate. He won’t say anything bad about him.” The crowd laughed. “Nikki can’t quite figure out whether she’s for him or against him, so until she’s firmly against him, he’ll say nothing bad about her. Mike Pence he’s deeply disappointed in, but he’s not spending time talking about him, either. He doesn’t think Mike can beat him.”

Yet, by design, most of Christie’s energy is devoted to the former president. This is only so effective without Trump there to react. “It is certainly made more complicated by the fact that he isn’t on the debate stage,” the adviser admitted. To address that problem, Christie plans to follow Trump onto the campaign trail, “going to where he is if he’s not going to come to the debate stage,” according to the adviser. The idea is to be “creative and nimble” to “draw a contrast” that positions Christie as Trump’s main antagonist and invites local media coverage of the two men together, elevating Christie’s profile. The adviser painted the hypothetical picture of Trump rolling into some town in America for an arena rally and Christie scheduling a press conference nearby three hours before it starts.

“In 2016, there was this feeling that it wasn’t real, that he wasn’t actually the front-runner, and there was a theory that we all lived in different lanes, and if you took somebody out in the lanes, ultimately you could be the last person standing to take out Trump,” his senior adviser told me. “Fundamentally, our view on this now is that you can’t repeat that play because it didn’t work. We’re not saying definitively that what we’re doing is going to work. But the strategy for us is to consistently and continually go after Trump, betting on the inevitability that something will shift because it’s just the law of physics.”

If that sounds like wishful thinking, it is, but as a matter of strategy, it reflects how much the stakes have lowered for Christie. The season of his political career in which he seemed like the future of the GOP is so far gone that it can be difficult to remember what that Republican Party was like or to believe it ever was that way. In this primary, he does not appear to have the time, the will, or the manpower to pick off everybody standing in his way, and even if he did, the rest of the field is so low wattage. Would anyone really care? If this doesn’t work, the campaign reasons, nothing will.

Donald Trump at a Nonunion Auto-Parts Factory

Clinton Township, Michigan

A few hundred fans lined up in the rain in Clinton Township, Michigan, on the evening of September 27 to watch as Trump’s motorcade sped down Capital Boulevard. At the sight of the beacons flashing red, white, and blue, a woman cried out, “He’s coming!” She joined the crowd as they chanted, “USA! USA! USA!” and “Freedom!”

Rather than attend the second Republican debate at the Reagan Library in Simi Valley, Trump had decided to campaign against President Biden outside Detroit. The previous day, Biden had walked the picket line with the striking United Auto Workers. Trump was taking a different approach, staging a rally inside Drake Enterprises, a nonunion automotive factory, for an audience of numerous nonunion workers. The campaign provided attendees with signs to wave in the air. They read UNION WORKERS FOR TRUMP.

Trump looked satisfied when he arrived onstage at 8 p.m. Eastern, an hour before the Fox Business debate was scheduled to begin. He posed campily for the duration of his walk-on music, Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the U.S.A.,” then engaged in the time-honored tradition of wildly overstating the size of his audience. “Outside, we have thousands and thousands of people,” he said. “Do you see what’s going on out there?”

Trump’s speech, read off the teleprompter, called for “a revival of economic nationalism and our automobile manufacturing.” The strike missed the point, he said. “I watched them negotiating the contract on the picket line, but it doesn’t make a damn bit of difference because in two years, you’re all gonna be out of business.”

Trump isn’t much of a plan guy, but it is now his strategy to ignore the primary whenever he has the self-control to do so. On this occasion, he mostly managed, with the exception of an aside about “Ron DeSanctimonious” (“You know, he tried to destroy Social Security”) and another about “the job candidates” (“You know, we’re competing with the job candidates. They’re all running for a job. No, they’re all job candidates. They wanna be in the, uh, they wanna — they’ll do anything. Secretary of something. They even say VP, I dunno. Does anybody see any VP in the group? I don’t think so”).

Unless and until the Republican National Committee accedes to his request and cancels the remainder of the debates, it is up to Trump to generate the impression that the only campaign he’s running is against Biden, though his insistence that he did not actually lose the 2020 election has tripped him up, slightly, on the trail. “The reason Crooked Joe and his thugs are trying so hard to stop me is that in my first term I disrupted all of it. Oh, did I disrupt. Was that — that was called major disruption,” he said. “And in my second term — which we’re sort of having now, but I don’t want the results, right? I don’t want the results of this second term. This second term is a disaster for this country — worst president, think of it, there’s never been a president like this … You look at what’s happening in this country, it’s horrible, but in my second term, we’ll finish the job and we’ll get rid of the cheaters, the liars, the scammers, and the criminals. They’ll lose their grip on power once and for all.”

By the time Trump Force One was wheels up and back to Palm Beach, the debate was almost over, and across the ideological divide there was rare agreement: It had been a disaster for all involved. If you don’t play, you can’t lose, but Trump’s decision to skip both primary debates proved you can sometimes win anyway.

After dinner from McDonald’s was served, Trump invited Henry Rodgers, the chief national correspondent for the Daily Caller, to his cabin to watch. “He was saying, ‘I just want to keep focused. I want to watch this and see how much of a shitshow it is,’” Rodgers told me. The whole thing seemed to amuse the candidate. “He’s just eating this up,” Rodgers said. “And he’s going to let them eat themselves alive.”

On the other hand, Trump worries. The longer the primary goes on, the less time he has to consolidate power and money. “He feels like the other candidates onstage are kind of just undermining his massive lead in the polls,” Rodgers said.

Still, Trump was in a good mood. It was, Rodgers said, the most enthusiastic he has seen him over the past several months, in which Rodgers has been invited to travel on the plane a total of three times.

“He’s going through a lot of shit this summer, but he benefits every single time,” one campaign staffer told me. “He’s like the best Trump I’ve ever, ever, ever, ever been around.” This was the first trip where Trump seemed eager to talk, Rodgers said, and to give him a tour of the plane. He even brought him to the cockpit, asking, “Henry, do you want to land the plane?”

Nikki Haley at a Suburban Events Center

Des Moines, Iowa

At 1:30 a.m. on Sunday, October 1, Marc Caputo, a reporter with The Messenger, received a text from a member of Trump’s 2024 campaign staff. The message contained a photo of a birdcage and a two-pound bag of Great Choice Fortified Canary & Finch Food, positioned on the carpet outside a door with a DO NOT DISTURB sign hanging from its handle. Sticking out from the metal bars of the cage was a note scribbled in marker: FROM: TRUMP CAMPAIGN.

The avian supplies were intended for Nikki Haley, the guest in Room 1122 at the Hotel Fort Des Moines. The former governor of South Carolina, Haley had served in Trump’s administration as ambassador to the U.N. and was now among his distant rivals for the nomination. Haley had performed well enough at the debates to earn favorable media attention and a small spike in the polls, and that was enough to activate the Nickname-Generating Artist Formerly Known As President of the United States.

“Nikki ‘Birdbrain’ Haley was exposed for her caustic DISLOYALTY & LIES about the Republican Party, and me,” Trump wrote on his social network, Truth Social, after the debate. “Doesn’t have what it takes, NEVER DID!” The dynamics of the primary are such that this development was received as its own kind of favorable poll. The Daily News headline on the matter: “Nikki Haley Draws Insults From Trump in Sign She Is Gaining Ground in Republican Presidential Race.”

With things looking up, Haley arrived in Iowa for a town hall in Clive, a suburb west of Des Moines. Her numbers in the flyover state had increased by an average of close to four percentage points over the course of the prior month. Now, she was in third place — just barely, but still — behind Trump and DeSantis. With her momentum, she had left fellow South Carolinian Tim Scott far behind. Scott, a sitting senator, is reasonably considered among the pack of at least distantly viable Trump challengers I spent time with on the trail — but he is losing altitude quickly, has nothing approximating a base, and seemed not quite worth chasing down in rural Iowa, where his presence was felt mostly through ads that depicted him standing awkwardly at the border wall. For this occasion, Haley’s campaign had booked the ballroom at the Horizon Events Center, a 600-person venue she was, according to the Associated Press, “hoping to fill.”

Inside, before a big blue curtain and a big American flag, the crowd snaked into rows of folding chairs encircling a small stage to the sounds of “NH 2024 Town Hall Playlist (Summer Updates),” Team Haley’s Spotify curation of boomer and Gen-X bops. ABBA, the Go-Go’s, Def Leppard, Blake Shelton, and so on. When a candidate experiences what the media calls “a moment,” the mysteriously flexile stretch of time when hype supplants indifference and anything seems possible, you know it. The moment announces itself with the vibrations of the room, with a certain tenor and alertness, and, most obviously, with the number of interested parties showing up. On this day, there was no such sense — only about 150 Iowans turned out, including two fratty hecklers, along with a handful of reporters, seven video cameras, and a few still photographers.

Haley emerged to the tune of “Eye of the Tiger,” long a staple of Trump rallies. She wore a crochet top, dark-blue jeans, and open-toe shoes with sky-high block heels. “I love music. You were listening to my playlist earlier,” Haley told the crowd. As she spoke, a young man interjected, “Excuse me! What do you think of Taylor Swift? Swiftie or not?” Haley was not amused. She didn’t respond. “Can we just get through this?” she said. She continued on with her remarks. Then she was interrupted again. “Nikki Haley’s not even a Swiftie!” She frowned. The crowd booed. Hand on her hip, frozen smile on her face, Haley watched in silence as security dragged the heckler out. Finally, she said, “I’ll say this: While that has been a distraction, how blessed we are to have freedom of speech in this country.”

That evening, when Haley arrived at the Hotel Fort Des Moines, it was crawling with Trump’s staff and Secret Service detail. Trump was 1,400 miles away, wrapping up his trip to California. He had flown through the Pacific Airshow in Huntington Beach and addressed the state GOP convention in Anaheim, and now he was hosting an evening fundraiser in Costa Mesa, where tickets ranged from $1,000 to $23,000 per pair for a “VIP reception” and a photo with the candidate.

Haley retired to her room on the 11th floor. By 2:45 a.m., when Trump disembarked from his private jet and boarded an SUV en route downtown, his team had succeeded in delivering their demented gift. They located Haley’s room, staged the objects, and snapped photos, all without alerting her to the activity taking place a few feet away from where she slept.

It was harassment, definitely. An invasion of privacy, a violation of personal space — a banal schoolyard taunt weaponized by socially underdeveloped and terminally online people with no manners and zero boundaries. Yet a birdcage is not a bear trap. It was too bizarre to be a threat but too creepy to be a joke.

In politics, though, if it’s not a liability, it’s an opportunity, and the Haley campaign saw in the event a certain poetry that might prove useful. In the story Haley the politician tells of Haley the protagonist, she has spent a lifetime confronting bullies. On Twitter, she shared an image of the scene, though she didn’t quite know what to say. “After a day of campaigning, this is the message waiting for me outside my hotel room …” She added a flourish of hashtags that seem unlikely to trend anytime soon: “#PrettyPatheticTryAgain #YouJustMadeMyCaseForMe.”

Although the Hotel Fort Des Moines had confirmed to the Haley campaign that the Trump campaign had indeed left the birdcage at her door, and although the Trump campaign volunteered proof that they were behind the stunt to The Messenger’s Caputo, they soon changed their minds. They no longer wanted credit. They wanted instead to fuck with Haley.

When I asked Trump adviser Miller about it, he said, “Nikki Smollett?” It was a reference to the actor Jussie Smollett, who was convicted of staging a fake hate crime against himself in Chicago in 2019. Subsequent inquiries to Trump world yielded similar results. “If Nikki really wanted attention, she should have just pulled the fire alarm,” the campaign said. “What? Are they saying it was us?” “This all seems very shady on their part,” and “Maybe Birdbrain should stop worrying about conspiracy theories and find a way to improve on her single-digit poll standing.”

“It’s another sign that he is threatened by Nikki’s rise,” Haley spokeswoman Olivia Perez-Cubas told me. That’s one interpretation. Another is that, after months of saying “Ron DeSanctimonious” (or “Ron DeSanctus” for short), Trump is experiencing what he has so often promised the American people they would feel. He’s tired of winning. He’s trolling Haley to feel something other than boredom.

More on the 2024 Presidential Election

- The Iowa Democratic Caucuses As We Knew Them Finally Die

- Capitol Hill Dysfunction Helps Trump, the Chaos Candidate

- With Trump’s 2024 Rivals Out, Who’s Left on His Veep List?