It was a routine ground ball, an easy double play, and the first baseman for the New York Mets did his job. He collected the bouncing ball, spun toward second base, gunned down the lead runner for the Cincinnati Reds, then waited as his teammate, shortstop Bud Harrelson, threw the ball back to first to end the inning.

The crowd at Shea Stadium roared. Fifty years ago today — October 8, 1973 — they had come to Queens to see their scrappy, underdog Mets beat the dominant, big-talking Reds in game three of the National League Championship Series, and now, improbably, it was happening. The Mets had a 9-2 lead in the fifth. They were about to move within one game of their second World Series in the past four years, and it seemed to be coming easy — something that felt very un-Mets-ian. As New York recorded the double play, the Mets infielders began to jog to the dugout, looking cool in their blue stirrup socks.

But the lead runner for the Reds — Pete Rose, 32 years old and already divisive, the sort of player fans either loved or hated — was intent on changing the entire narrative. Rose was going to slide hard into Bud Harrelson at second, pop up, and maybe throw an elbow at him for good measure.

These days, Rose can’t seem to decide which version of the story he likes best. Sometimes, he argues that he was just doing what he always did. He was living up to his nickname, “Charlie Hustle.” He was playing hard. “You know how many second basemen or shortstops I knocked on their ass in my career?” Rose asked me once. “Bud Harrelson was just another one.”

Other times, often in the same conversation, he suggests that he was intentionally trying to take out Harrelson, that he was upset about Harrelson talking trash the day before, that he needed to send a message to Harrelson — a much smaller man, 50 pounds lighter than Rose, with far more limited talents — and that he didn’t care if he started a fight because Harrelson was out of line. “When you’re a 150-pound shortstop — and you’re in the playoffs — don’t say things to ignite the opposition,” Rose said as a sort of warning decades later. “You understand what I’m saying?”

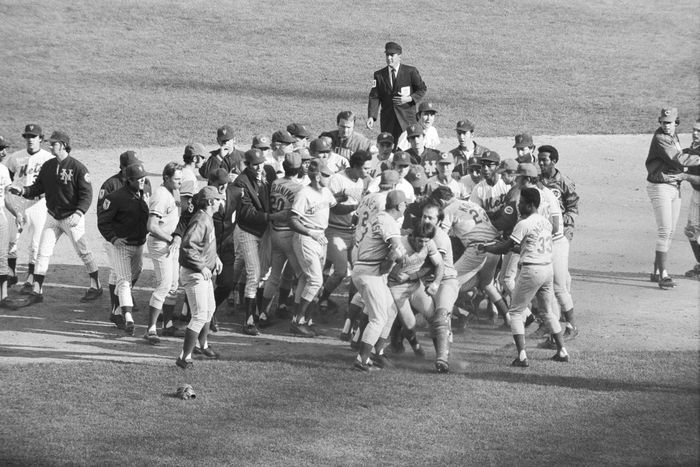

The epic brawl that followed Rose’s aggressive slide cleared both benches, incited New Yorkers at the stadium to pelt the field with garbage for minutes to come, nearly forced the Mets to forfeit when a whiskey bottle came flying out of the upper deck and almost hit Rose in the head in left field, and revealed something important about baseball at the time.

The sport was neither perfect nor polished, and that was why people loved it. Despite the chaos on the field that day after Rose and Harrelson tumbled into the dirt at second base, not a single player would be ejected, suspended, or punished in any way — an outcome that is impossible to imagine today.

“Baseball to me during that time was a spirited and rugged sport — not a passive and gentle sport like we see most of the time now,” said Cleon Jones, the Mets left-fielder during the playoffs in 1973. “It was a different game.”

The problem between Rose and Harrelson began before the 1973 playoffs had even started. It was about respect. In the regular season that year, the Reds won 99 games while the Mets goofed around for most of the summer and finished a meager three games over .500. These two teams were both division winners, but they weren’t equals, and Rose seemed insulted that the press dared to even suggest the Mets had a chance against the Reds. “I’m just scared to death,” Rose said sarcastically before the series.

Then, the Reds nearly lost game one in Cincinnati and got shut out in game two, and in the locker room Bud Harrelson couldn’t stop himself from offering his opinion about what was ailing Cincinnati. He told reporters that it looked like the Reds were swinging from their heels.

Rose and Harrelson had enjoyed a good relationship over the years. Rose, one of the league’s best hitters, had offered tips to Harrelson when the Mets shortstop, a career .240 hitter, was struggling at the plate. And Rose had once told Harrelson that his defense would improve if he used a smaller glove — advice that proved correct.

But advice for Rose was typically a one-way transaction. He’d give it; he wasn’t going to take it, especially not from a player who was clearly inferior to him. And when a reporter told him what Harrelson had said about him and his teammates, Rose lashed out. “That little cocksucker,” he said. Or maybe it was “little motherfucker.” The newspapers couldn’t print the actual words. Then, in the Reds clubhouse, Rose sprayed Harrelson’s comment around like lighter fluid.

“You’re hitting off your heels,” Rose told his teammates, seething with still more sarcasm, before game three. “Harrelson, the batting coach, says we’re all batting off our heels.”

So, no — this wasn’t an ordinary slide into second base that afternoon in October 1973. “This was intentional,” recalled Mets outfielder Ed Kranepool. “There was no reason for it.” Rose was out by 15 feet. “And he just kept running,” Kranepool said.

On impact, Rose and Harrelson exchanged words, cursed some more. “And I just grabbed him,” Rose told me later. “I just grabbed him. And then Wayne Garrett came in from third, and he started the whole mêlée.” Garrett, the Mets third-baseman, was just trying to protect the much smaller Harrelson. But Rose liked to blame Garrett for what happened next: multiple fights at second base, players throwing sucker punches in the pile, and Reds reliever Pedro Borbon swinging at anyone in a blue hat. “Guys scattered all over the place,” recalled Jon Matlack, a pitcher for the Mets who was in the pile trying to peel guys apart. “There were fights on the field from a couple of guys.”

When it was over, there were hats strewn everywhere, and Borbon accidentally placed a Mets cap on his head — a mistake that enraged him so much that he took his frustration out on the hat itself. “He started biting it and ripping it,” recalled Tony Pérez, Rose’s Hall of Fame teammate. Borbon was acting, Pérez said, “like a dog,” while the fans behaved even worse. For minutes afterward, they threw trash at Rose, including that bottle of whiskey, and gave Reds manager Sparky Anderson no choice but to pull his team off the field.

“I’m taking my men out of here,” Anderson barked at the umpires. “Pete Rose has done too much for baseball to die in left field.”

The players didn’t think much of it at the time. “It was just another day at the ballpark,” Pérez said. “That’s the way baseball was played 50 years ago,” Jones agreed. But looking back on it now, the players who were there, the men in the fray at Shea Stadium, realize that it was one of the last moments in baseball history when anything like this would be tolerated. Changes were coming that would alter the sport forever: the dawn of free agency a year later; the security of multiyear contracts for the first time in players’ lives; the injection of big money into the game by the late 1970s; the riches of billion-dollar television deals by the 1980s; and a raft of new rules and edicts intended to protect players — in whom the owners had invested millions of dollars.

In this new world, players are safer. Runners can no longer barrel into the catcher at home plate like they once did, another Pete Rose speciality. Pitchers who choose to throw at a batter — or place a sizzling fastball on the inside part of the plate — are likely to be ejected. And sliding hard into second base, and fighting over it, has also been all but litigated out of the game. A far-less-violent slide at second base this summer in a game between the Cleveland Guardians and Chicago White Sox led to six ejections and two suspensions.

But these changes have also made the game more predictable, and other trends, including surging strikeout rates and declining batting averages, have made the game slower. As a result, fans have started to tune out. Two of the past three World Series have recorded the lowest television ratings in modern history, and this year Major League Baseball intervened to help correct the problem. In 2023, newly installed pitch clocks have shortened games by nearly a half an hour, while larger bases have encouraged movement. Stolen-base totals this season reached a level not seen since the late 1980s. Perhaps these changes will drive higher ratings this fall. Or maybe fans will tune back in for the teams on the field: the offensive power in Atlanta; the Cinderella story in Baltimore; or the mania in Philadelphia.

What isn’t likely, however, is anything like the scene at Shea Stadium in October 1973, the chaos on the field, and the anger in the stands. Bud Harrelson, who suffers from dementia and no longer does interviews, and Pete Rose, who was banned from the game in 1989 for gambling and has courted controversy ever since, were part of something back then that isn’t likely to happen ever again. Not in New York, not anywhere.

At the time, both Rose and Harrelson just wanted to get back on the field, resume play, and they finally did. New York manager Yogi Berra sent a contingent of Mets players to the outfield to bargain with the fans. The fans ultimately stopped throwing trash at Rose. New York won game three without further incident and then won the pennant two days later in yet another scene that’s hard to imagine today. As the Mets recorded the final out, thousands of fans stormed the field in Queens, forcing players to run for their lives just to make it to the dugout.

It was raw. It was wild. It was dangerous.

It was baseball.